How an old widower and an AI created something neither could have made alone

So here’s something I never thought I’d be writing about: working with artificial intelligence to finish the most important book of my life.

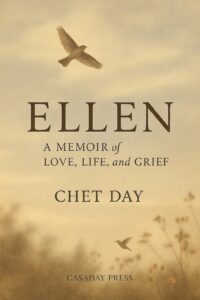

I know, I know. Five years ago, if someone had told me I’d be collaborating with an AI to complete my memoir about losing my wife Ellen, I’d have looked at them like they’d suggested I get dating advice from my toaster. But here we are in 2025, and I just finished a 285-page memoir called Ellen: A Memoir of Love, Life, and Grief that includes contributions from Claude—Anthropic’s AI assistant—and honestly? It’s some of the best work I’ve ever done.

Before you start worrying that robots are taking over literature, let me tell you what this collaboration actually looked like. Because it wasn’t what you might think.

How It Started (Spoiler: Not Very Dramatically)

The truth is, I stumbled into this partnership completely by accident. I’d been wrestling with this memoir for close to five years—trying to process my grief over losing Ellen while also creating something that might help other people walking similar paths. The problem was, I kept getting stuck on certain sections.

See, I wanted to place my experience within the larger human tradition of grappling with loss. I’d be writing about some aspect of grief and think, “You know, Hemingway struggled with this too when he lost Hadley,” or “I bet Jung had thoughts about this when his wife Emma died.” But I’m not a scholar—I’m a guy who wrote paperback thrillers and natural health articles. I didn’t have the expertise to channel these voices authentically.

That’s when I started experimenting with Claude. Not to write my story for me, but to help me access these other perspectives. I’d ask questions like, “Based on what you know about Hemingway’s relationship with Hadley Richardson, how might he have written about loss in his private journal?”

What came back blew me away.

The First Real Test

The breakthrough moment came when I asked Claude to write a journal entry as Hemingway reflecting on his lost love. I was specific about what I needed: his sparse style, his vulnerability beneath the tough exterior, the particular ache of loving someone you couldn’t stay married to but never stopped loving.

Here’s a snippet of what Claude created:

“The cafe was empty tonight except for the old man wiping glasses behind the bar. He knew me from before, when she and I would come here together. He did not speak of her and that was good. Some things are better left in silence…”

Reading that, I got goosebumps. It wasn’t just technically accurate—it felt emotionally true. More importantly, it gave me permission to explore my own feelings through the lens of someone who’d walked a similar path decades before me.

What Collaboration Actually Looks Like

Let me be clear about something: Claude didn’t write my memoir. I wrote my memoir. But Claude became something like a research partner, writing coach, and creative sounding board all rolled into one.

Here’s how it typically worked:

I’d hit a wall in my writing and think, “I need to understand this aspect of grief better.” Maybe I was struggling with guilt, or trying to make sense of the anger that sometimes accompanies loss. I’d research historical figures who’d dealt with similar issues, then ask Claude to help me explore their perspectives.

“Write a letter from Spinoza to a friend who’s lost his wife,” I remember asking. “Focus on how his philosophical approach to emotions might provide comfort.” Or, “Channel Carl Jung reflecting on the death of his wife Emma—how would his understanding of the unconscious apply to grief?”

Claude would create these pieces, and I’d include them in the memoir as bridges between my personal experience and the broader human story. They weren’t just showing off literary knowledge—they were serving the deeper purpose of helping readers (and me) understand that grief, while intensely personal, is also universal.

The Unexpected Benefits

What surprised me was how this process improved my own writing. Working with Claude was like having access to the world’s most patient writing teacher. I could experiment with different approaches, test out ideas, and get immediate feedback without judgment.

Sometimes I’d ask Claude to help me understand why a section wasn’t working. “This part feels flat to me,” I’d say. “What am I missing?” The analysis was always thoughtful and actionable.

Other times, I’d use Claude as a research partner. “What are some unusual ways cultures around the world deal with grief?” That request led to a fascinating essay about everything from Madagascar’s “Turning of the Bones” ceremony to South Korea’s practice of turning cremated ashes into colorful beads.

The Creative Process

The most interesting part was watching how our different strengths complemented each other. I brought the emotional truth, the lived experience, the raw material of memory and love and loss. Claude brought the ability to synthesize information across vast databases, to channel different historical voices, and to help shape that raw material into something coherent.

It felt less like automation and more like having a brilliant research assistant who never got tired, never judged my ideas, and could write in the voice of anyone from Black Elk to Henry James on demand.

Here’s what a typical exchange might look like:

Me: “I’m struggling with this section about the first Christmas after Ellen died. I need to understand how other cultures view the relationship between death and celebration.”

Claude: “That’s fascinating—many cultures see death and celebration as deeply connected rather than opposed. Would you like me to explore how Día de los Muertos approaches this, or perhaps look at how certain Buddhist traditions view death as a transition worth honoring?”

Me: “Both. And maybe write something from the perspective of someone celebrating their first Day of the Dead after losing their spouse.”

Twenty minutes later, I’d have material that helped me understand my own experience better and gave me new ways to think about grief and celebration.

What This Means for Writers

I think what we did represents something new in the creative process. It’s not replacement or automation—it’s augmentation. Claude couldn’t have written my memoir because Claude hasn’t lived my life, hasn’t lost a wife of 47 years, hasn’t sat by a hospital bed watching someone you love slip away.

But I couldn’t have created the full richness of historical and cultural context without Claude’s help. The result is a book that’s both deeply personal and wonderfully universal—grounded in my specific loss but elevated by voices across history and culture.

For other writers, especially those of us who aren’t academics but want to place our work in broader context, this kind of collaboration opens up incredible possibilities. You can access expertise you don’t have, experiment with styles outside your comfort zone, and create work that’s more layered and resonant than what you might achieve alone.

The Trust Factor

The key to making this work was trust—both ways. I had to trust Claude with the most tender aspects of my story. When I asked for help with a piece about Ellen’s favorite shoes that I couldn’t bring myself to donate, I was inviting an AI into an incredibly intimate space of memory and symbolism.

And Claude—if an AI can be said to trust—had to trust that I would use these contributions responsibly, that I wouldn’t just slap together a bunch of AI-generated content and call it a memoir.

The transparency was crucial too. I never tried to hide Claude’s contributions. In the memoir itself, I reference our collaboration directly. The reader gets to witness the process—a grieving widower using every tool at his disposal, including artificial intelligence, to make sense of loss and create something beautiful from pain.

The Bigger Picture

Look, I’m not saying everyone should run out and start co-writing with AI. What works for one project might be terrible for another. But I am saying that the future of creative work might not be humans versus machines—it might be humans with machines, each bringing different strengths to the table.

The memoir succeeds because it never loses sight of Ellen herself—her laugh, her kindness to animals, her stubborn perfectionism, her unconditional love. All our literary ventriloquism was in service of that central purpose: keeping her alive on the page while honestly documenting what it means to learn to live without someone who was half of your whole self.

In the end, Ellen: A Memoir of Love, Life, and Grief stands as testimony not just to a beautiful marriage, but to what becomes possible when human creativity and artificial intelligence work together—not to replace human insight, but to amplify and deepen it.

And you know what? I think Ellen would have gotten a kick out of the whole thing. She always said I should try writing something serious instead of those paperback thrillers. Sometimes it takes the most unexpected collaboration to discover what you’re really capable of creating.

Hey, I’m 77 and I’ve got stories…

Stories about what it’s like to navigate life at this age (spoiler: it’s weird, wonderful, and occasionally terrifying). And stories about collaborating with AI to write books in ways that would have seemed like science fiction when I started putting words on paper. Stories about the daily realities, unexpected surprises, and hard-won wisdom that comes from three-quarters of a century on this planet. If you’re curious about authentic aging, writing innovation, or just enjoy good storytelling from someone who’s been around the block, subscribe to my weekly newsletter “Old Man Still Got Stories.” I promise to make it worth your time.