Five years writing a grief memoir…

That’s how long I spent writing about my life with Ellen, my wife of 47 years who died on Thanksgiving Day 2019. Five years of wrestling with memories, confronting regrets, trying to honor a complicated woman and an even more complicated marriage. Five years of starting over, deleting thousands of words, questioning whether I was smart enough or talented enough to write something she’d be proud of.

And here’s the part that’s going to make some of you uncomfortable: I didn’t do it alone. About 15% of the final manuscript was created with significant help from Claude, an AI assistant. Not ghost-written. Not generated by typing prompts into a machine. But genuinely collaborative in ways I’m still processing.

This is the story of that five-year journey, what I learned about grief and writing and perfectionism, and why inviting an AI into the most personal project of my life might have been the smartest—or strangest—decision I ever made as a writer.

The Project Ellen Would Have Wanted (And Also Hated)

Let me start by telling you about Ellen.

(1948 – 2019)

She was brilliant. Completed her graduate coursework in English literature with high honors. Started a dissertation on Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale that her advisor said was original and would land her a job at a top university. That was the plan—she’d finish her PhD, get a faculty position, and I’d finally have time to write those bestselling novels I was so confident I could produce.

Except Ellen never finished her dissertation.

She was the kind of perfectionist who kept expanding the project instead of narrowing in on completion. New ideas would emerge during the writing, connections she hadn’t seen before, and suddenly the dissertation needed another chapter, another revision, another year of work. I’d stay up nights typing her papers (this was before word processors), and she’d get new insights mid-typing and we’d have to start over.

It drove me crazy. My philosophy has always been “good enough is good enough—turn it in and move on.” Hers was “keep working until it’s as perfect as your mind can make it, even if that takes forever.”

Guess Which One…

Guess which one of us never finished her dissertation? Then take a shot at which approach I had to learn to respect, even when it frustrated the hell out of me?

Now here’s the cosmic joke: when Ellen died and I decided to write a memoir about our life together, I turned into her. The book I thought would take six months became a five-year obsession. What started as a simple collection of sweet memories morphed into something increasingly complicated—part tribute, part honest reckoning with a complicated marriage, part meditation on grief and regret and the meaning of a life shared.

I often felt like I was wrestling the manuscript in a tub of cold jello. I wrote thousands and thousands of words that got deleted. The project kept expanding instead of narrowing. I couldn’t figure out how to frame it, where to put the focus, what story I was actually trying to tell.

I’d become the perfectionist I used to be impatient with. Funny how that works.

Tolkien, Niggle, and the Purgatory of Creation

Four years into the project, still stuck, I just happened to discover Tolkien’s short story “Leaf by Niggle.”

If you don’t know it, here’s the relevant part: Niggle is a painter obsessed with capturing a single tree on canvas, getting every leaf perfect, constantly interrupted by mundane obligations but unable to let the painting go. He dies before finishing it. The story’s second half takes place in a kind of purgatory where Niggle finally sees his tree—his incomplete, imperfect tree—made real and whole in ways he never imagined possible on earth.

The story gutted me.

Because that’s exactly what I was doing. Obsessing over getting Ellen’s memoir perfect. Trying to capture every leaf on this impossible tree I was painting. Spending years in a kind of creative purgatory, revisiting memories both beautiful and painful, confronting things done and not done properly, questioning whether I’d ever finish or whether I’d die with this manuscript incomplete like Ellen’s dissertation.

The parallel to my own experience was eerie. Tolkien wrote “Leaf by Niggle” after a serious illness when he feared he might die before finishing The Lord of the Rings. I’m 77 now. I started this memoir at 72. Death isn’t an abstract concept anymore—it’s a neighbor I see every morning when I walk past the houses of the other widowers in my neighborhood.

Would I finish Ellen’s memoir before I joined her? Would I get to see my tree completed, or would this project remain forever unfinished like her dissertation?

When AI Became My Collaboration Partner

Here’s where the story gets interesting, and where I suspect I’ll lose some of you.

Almost five years into the project, I had a compelling idea: adding sections to the memoir written from the point of view of both living and dead writers, poets, philosophers, even scientists might finally give me the hook I needed to excavate the depths of grief that I didn’t have the smarts or the skill to mine. Since I didn’t have the skills or the detailed knowledge, I decided to turn to Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet AI to see if it could write drafts of these imagined sections for me to review and then either use or discard.

To clarify, the memoir needed supporting material—contextual pieces that would help readers understand grief more broadly, that would place my personal experience within the larger landscape of human loss. I’m a thriller writer by training. I can plot a creepy story. I can write snappy dialogue. But crafting imaginary journal entries from Hemingway or Mark Twain grappling with grief? Writing historical letters of condolence in the voice of Spinoza? Creating poems about loss that felt authentic but weren’t mine?

When You Need Help…

That’s not in my skill set.

So I asked Claude to help. And what emerged was something I hadn’t anticipated—a genuine creative collaboration.

I’d provide the concept: “I need a journal entry from Jung reflecting on the death of his wife.” Claude would create a draft. I’d read it, feel whether it worked emotionally in the context of my narrative, ask for revisions, push back on phrasings that felt wrong. We’d go back and forth until we had something that served the larger purpose of the memoir—enriching my personal story with broader perspectives on grief and loss.

The result? About 15% of the final manuscript consists of these supporting materials—journal entries, letters, poems, brief essays—all created through this collaborative process.

The Authenticity Question (And Why It’s Complicated)

I know what some of you are thinking. “That’s not real writing. That’s cheating. How can you claim this memoir is authentic if a machine wrote part of it?”

Fair question. Let me complicate it for you.

Ellen’s memoir is the most emotionally authentic thing I’ve ever written. Every memory, every moment of grief, every painful recognition of my failures as a caregiver—that’s all me, straight from the heart, no AI assistance. The core narrative is 100% human.

But here’s the thing: I wanted the memoir to be more than just my personal story. I wanted it to be useful to other grievers. I wanted it to place my specific loss within the broader context of how humans have always grappled with death and grief. That required perspectives and voices I couldn’t provide on my own.

Could I have spent years learning to write convincing historical letters and journal entries? Sure. Would that have made the book more “authentic” somehow? I honestly don’t know.

What I do know is this: Claude’s contributions helped me create a richer, more textured memoir than I could have created alone. The imaginary Hemingway journal entry helped me articulate aspects of masculine grief I was struggling to express. The Spinoza letter gave me language for philosophical dimensions of loss that were beyond my ability to capture. The poems about grief created emotional resonance at key moments.

Were these “real”? They felt real to me. They served the truth I was trying to tell, even if they weren’t created by my hand alone.

What “Good Enough” Actually Means

Remember Ellen’s perfectionism? Remember how she could never finish because there was always one more revision, one more insight, one more connection to explore?

Working with Claude helped me understand something about perfectionism that I’d never grasped when I was watching Ellen struggle with her dissertation: sometimes perfectionism isn’t about making something perfect. It’s about fear. Fear that if you call it finished, it might not be good enough or fear that people will see your work and find it lacking. Fear that you’re not smart enough, talented enough, worthy enough to produce something of value.

I carried all those fears into Ellen’s memoir. I’m not a literary writer. I’m a guy who wrote paperback thrillers. Ellen always wanted me to write something serious, something with literary merit. When she died, this memoir became my chance to write the serious book she’d always wished I would write.

Am I Smart Enough?

But what if I wasn’t smart enough? What if I couldn’t write at the level a memoir of our life together deserved?

Here’s what the five-year journey taught me: “good enough” doesn’t mean settling for mediocrity. It means recognizing when additional revision starts being about fear rather than improvement. It means trusting that the work you’ve done—imperfect as it is—has value.

The joy I finally felt when I could see the memoir’s completion wasn’t about achieving perfection. It was about reaching a place where I could say: “This is what I have to offer. This is my tree, painted with whatever skill I possess. It’s finished.”

And here’s the profound part: that satisfaction transcends any concern about whether the memoir finds readers, whether it gets reviewed, whether it leaves a legacy. Doing the work itself—wrestling those five years with memory and grief and language—that’s what mattered. The transformation it created in me is the real achievement.

The Technical Questions about Writing a Grief Memoir

Okay, let’s get practical. If you’re curious about AI collaboration for your own memoir or writing project, here’s what I learned:

- What worked: Using AI for supporting material that enriched the main narrative. Claude created content that required skills I don’t have—historical voice, poetic language, philosophical reflection. This freed me to focus on what I do well: straightforward narrative, emotional honesty, storytelling.

- What didn’t work: Any attempt to have AI write my personal memories. I tried once, early on, describing a memory to Claude and asking for a draft. The result was technically competent but emotionally dead. My memories have to be in my words or they’re lies.

- The transparency question: I was clear from the beginning that I’d acknowledge AI’s contribution. The memoir’s foreword explicitly states that less than 15% was created with an AI language model, and I explain exactly how that collaboration worked. I’m not trying to pass off AI-generated content as entirely my own work. That would be dishonest.

- The control question: Every piece of AI-generated content went through multiple revisions based on my direction. I made all final creative decisions. If something didn’t serve the memoir’s larger purpose, it got cut regardless of how well-crafted it was. The AI was a tool, not a co-author in the traditional sense.

- The future question: I genuinely don’t know if AI collaboration will become standard in memoir writing or if it’ll be seen as a weird experimental phase we look back on with embarrassment. What I do know is that for this particular project, at this particular moment in my life, it helped me create something I couldn’t have created alone. On my 77th birthday—January 2025, five years after starting this project—I wrote the final words of Ellen’s memoir.

Surprised by the Ending…

The ending surprised me. I’d planned to conclude with fetching her cremated remains from the funeral home. But when I brought her home and set the cardboard box on my desk, fragments of a poem started appearing. Not from me, exactly, but from that mysterious place where language sometimes emerges without conscious effort.

That poem became the actual ending. Unexpected. Imperfect. But true.

I thought about Niggle again. About how in Tolkien’s story, the painter finally gets to see his tree—the one he’d labored over his whole life, never finishing, never satisfied—made real and complete in ways he couldn’t have imagined when he was obsessing over individual leaves.

That’s what happened with Ellen’s memoir. I’d spent five years wrestling with it, never quite satisfied, always seeing ways it could be better. But when I wrote that final poem and knew I was done, I experienced something like what Niggle must have felt.

The memoir isn’t perfect. It’s a 77-year-old thriller writer’s attempt to capture a complicated 47-year marriage and process his grief. It includes imaginary journal entries and AI-assisted poems alongside my own memories and reflections. It’s messy and experimental and probably breaks several unwritten rules about what memoirs should be.

But it’s finished. It’s true, as true as I could make it. And it exists now, independent of whether anyone reads it.

That’s enough.

What This Means for Writing a Grief Memoir

If you’re working on your own memoir—whether about grief or any other significant life experience—here’s what I learned that might help:

- Let go of perfectionism. Not by settling for mediocre work, but by recognizing when you’re revising out of fear rather than genuine improvement. Ellen never finished her dissertation because she couldn’t call anything done. Don’t let that be you.

- Consider all your tools. AI collaboration isn’t for everyone, and it shouldn’t be. But if there are aspects of your memoir that require skills you don’t have, consider whether technology might help you achieve your vision. Just be transparent about it.

- Trust your emotional truth. The parts of your memoir that come from direct personal experience need to be in your voice, with your words. That’s non-negotiable. But supporting material, contextual elements, things that enrich the narrative without being the narrative—there’s more flexibility there.

- Remember why you’re writing. On the hard days—and there will be many—reconnect with your purpose. For me it was honoring Ellen and helping other grievers. What’s yours? Let that guide your decisions.

- Define success on your own terms. My memoir will probably sell a few hundred copies to family and friends and random readers who stumble across it. That’s fine. The real success was completing it, processing my grief through writing, and creating something Ellen would recognize as serious work. Your success metrics will be different. That’s how it should be.

The Tree Is Real Now

There’s a line from Leonard Cohen that I included near the end of Ellen’s memoir: “Poetry is just the evidence of life. If your life is burning well, poetry is just the ash.”

Five years of writing Ellen’s memoir was evidence of a life burning. The grief burned. The love burned. The regret and the gratitude and the terrible recognition that I’d never fully appreciated her while she was alive—all of it burned.

The memoir is the ash. The evidence that something intense and transformative happened. That’s all any piece of writing ever is—evidence that someone was here, felt these things, tried to make sense of the chaos.

Whether you use AI or not, whether you’re a perfectionist like Ellen or a “good enough” person like me, whether you finish in six months or six years—if you’re writing memoir, you’re doing the same thing Niggle did. You’re trying to capture something true on the page. You’re painting your tree.

And here’s what I learned after five years: the tree becomes real not when it’s perfect, but when you finally stop working on it and let it stand.

Mine is standing now. Imperfect. Collaborative. Human and machine and memory and grief all tangled together.

But real. Finally real.

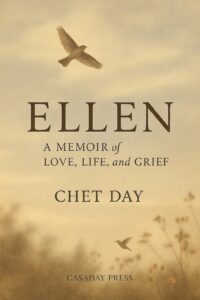

Ellen: A Memoir of Love, Life, and Grief by Chet Day is available now on Amazon Kindle. Click here to check it out.